A Liberating Lament

Where are the sanctuaries for Black people in America? Where can we go to be free, to breathe, to laugh, to love and be loved, and be human without the fears and threats of being harmed? For many, the answer has largely been the Black church.

Enslaved Blacks in America found a place called Brush Arbors. It was a safe haven hidden in the woods where (the) enslaved would steal away to pray, encourage one another and imitate life rituals such as marriages, baptisms and rites of passages for their children, and plot escapes for their freedom. Here in these sanctuaries, lamentations were liberating. Wailing released shackles. Weeping was an act of purging and resistance. And deep moans offered healing balms for the disinherited.

In the Brush Harbors of the clearing or the sanctuary of the forest, the oppressed offered all they had to give in collective work and responsibility with an urgency to love ourselves, to love our Black bodies, our Black skin, to love the very essence of our humanity and to insist, yes, our Black lives matter. We have always had the audacity to believe imaginatively. Our divine imagination is an offering of prayer. Perhaps that is our secret power – to believe in our worth even if our reality that we live and face each day has yet to prove this is true. We must declare it until it is realized. This is non-negotiable as precious lives are at stake and too many have already been stolen from us – choked to death, beaten to death, shot to death and left fully exposed to the elements like strange fruit, even in the sacred places we call our sanctuaries or houses of worship.

5th Anniversary

Wednesday evening, June 17, 2015 in the low country of Charleston, SC, not far from the rich Gullah sea islands where I grew up, tragedy struck the Black church once again. The rural setting, and its front porches with oversized swings made for more than a pair, invited us to steal away from our worries and sit awhile with our loved ones to sip tea and chill in the breeze. This was where my cousins and I would conjure dreams for the future. It was home base in tag or hide and go seek. We watched weddings from this porch and family reunions and held crab cracks. This was our clearing to return to as we grew older, perhaps retired with children of our own. This was not to be.

A visitor sat close to her when he entered the church that Wednesday night. My late cousin, Rev. DePayne V. Middleton was among the nine parishioners the self-proclaimed white supremacist murdered as the group gathered for Bible Study in the historic Emanuel AME Church in downtown Charleston. Mother Emanuel is steps away from the old Citadel in one direction and the old port and market in the other that both profited from human cargo. The church was once the parish for revolutionary abolitionist Denmark Vesey. Such coincidence of history and time intermingling narratives as a sacred sanctuary was once again violated and innocent lives forced into martyrdom.

Deeply aware of their heritage as a church birthed out of the liberation theology movement, hospitality and love remained at Emanuel AME’s core. So, on that night, when a stranger entered their midst, they offered one of the humblest and beautiful offerings one can extend to a stranger – a seat at the table.

When he entered the room, they did not attach stereotypes to him. They did not judge him or presume he was a threat because of his race. The stranger was welcomed to join in worship, prayer and fellowship. He was treated as a guest. My cousin reportedly shared a bible with him and as a result was one of the first to fall to the murderous act. When word came out of a shooting at the church; I called my cousin’s cellphone incessantly even as my gut told me there would not be a response. Even now, I can’t get the image out of my head of her ringing phone next to her lifeless body. How I wish I could have been transported, through the phone, to be by her side. Twelve people gathered there that night. Three survived; nine did not.

Say Her Name

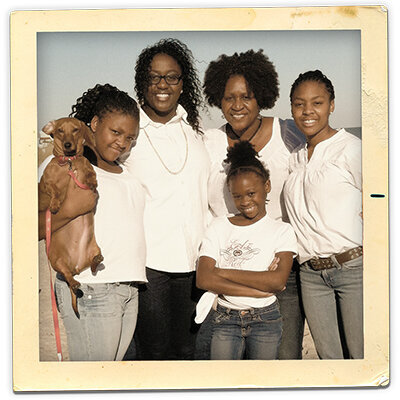

Rev. DePayne V. Middleton, a devoted mother of four dynamic daughters, an unapologetic person of faith, a brilliant vocalist and the most loyal among family and friends, did not get to go home to her four girls that night. They did not get to have one last dinner with their mommy and confidant. But the shooter who stated he wanted to start a race war, was afforded a free meal by police officers from a fast food restaurant before he was even taken into custody. My cousin’s body was still on the floor of that church when the assailant was captured. As our family mourned for her and waited to claim her body, he in his white privilege received the courtesy of a meal by police.

Radical Hospitality and Righteous Rage

We can be committed to love and radical hospitality, welcoming the stranger into our midst, and extending a seat to join us at the table. And we have a right to be angry or to righteously resist the violence against our humanity. To insist on a narrative of forgiveness is dehumanizing and violent and goes against the very nature to lament. As Christians, we celebrate the donning of ashes and sackcloths as priestly acts of lamentations and mourning; but denied families, in a watershed moment of grief, this right.

My family did not grant forgiveness in the courtroom. The words of a few became the headline for all and it became a marketable narrative that was made for television and made for profit, pulpits and politics, to ease the guilt and remove accountability from white supremacy. In the impetuous rush to force this false narrative, our society failed to radically engage dialogue on race, racism and racialized violence targeting Black and Brown bodies in America.

When we are denied our very right to grieve and to lament, those narratives forcing us into a stage of forgiveness before true reconciliation has taken place, are just as egregious and suggests our lives do not matter, not even to us. To insist that we forgive before we have been granted the dignity to grieve, claim the bodies of our loved ones and offer proper rituals of last rites is a breach of trust by all who exploited that narrative for their own gain. I thought of the way the Black church was attacked and how Rev. Jeremiah A. Wright, Jr. was demonized and abandoned for lamenting the sins of America following September 11. Wright was demonized and Trump elevated. When will we learn?

The Process and Privilege of Forgiveness

I do not forgive the man who killed my cousin. I choose righteously to lament.

Five years ago, when those bodies were stolen from us, we had a right and a duty to lament. It was a Kairos moment that did not call for convenience, but the inconvenience of truth telling. We were called to seize that moment in the global spotlight to expose the sins of this land, the city, state, those who played politics with our loss and even the church. The history of the Black church is interwoven in every civil rights and labor movement in this stolen and blood-stained nation. And I can say as a faith leader and organizer in this 21st Century movement for Black lives, that there is a role for the faith community to link arms with one another and refuse to look away and earnestly face the painful reality that we as Black bodies in America do not have the privilege or choice to escape. I prayed there would not be another Emanuel, but we were not the last faith community to lament such tragedy. Others would follow and with each new city and their mosques, synagogues or sanctuaries of faith violated by the shockwave of such violence; my protracted reality of trauma resurfaced. Where are the safe havens for Black and Brown bodies in America?

My lament does not make me less Christian and it does not disqualify me as a woman of the cloth. But it certainly affirms my humanity and rejects the moral injuries that plague our society. My lament draws me closer to Christ, whose ministry clearly is on the side of the oppressed and is the antithesis of racism, classism, and systemic and systematic abuse of power. Christ lamented, too.

My heart still trembles and aches from the loss of my cousin DePayne – our sweet, beautiful song bird Dep, and the litany of names of ancestors who join a roll call of hashtags. Forgiveness is not a part of my narrative at this time, and I am at peace with this, because it is my process of healing and reconciling. Yet, I proclaim, there is hope for our humanity, in the witness of DePayne’s four remarkable daughters who will tell their mother’s story, honoring her wholeness in body, mind and spirit—all of her, divine in the image of God.

Lest we forget. Ase.

Rev. Dr. Waltrina N. Middleton

Executive Director

Community Renewal Society

This is an excerpt of an article, I don’t forgive the man who murdered my cousin DePayne at Mother Emanuel, published via The Christian Century. Rev. Dr. Middleton speaks to the lives stolen by nationalist white supremacist domestic terrorism in America and its impact on those who remain to tell the truth. The full article will be printed in Christian Century’s July publication.