Reflections on September, 2001 After Twenty Years

By John H. Thomas

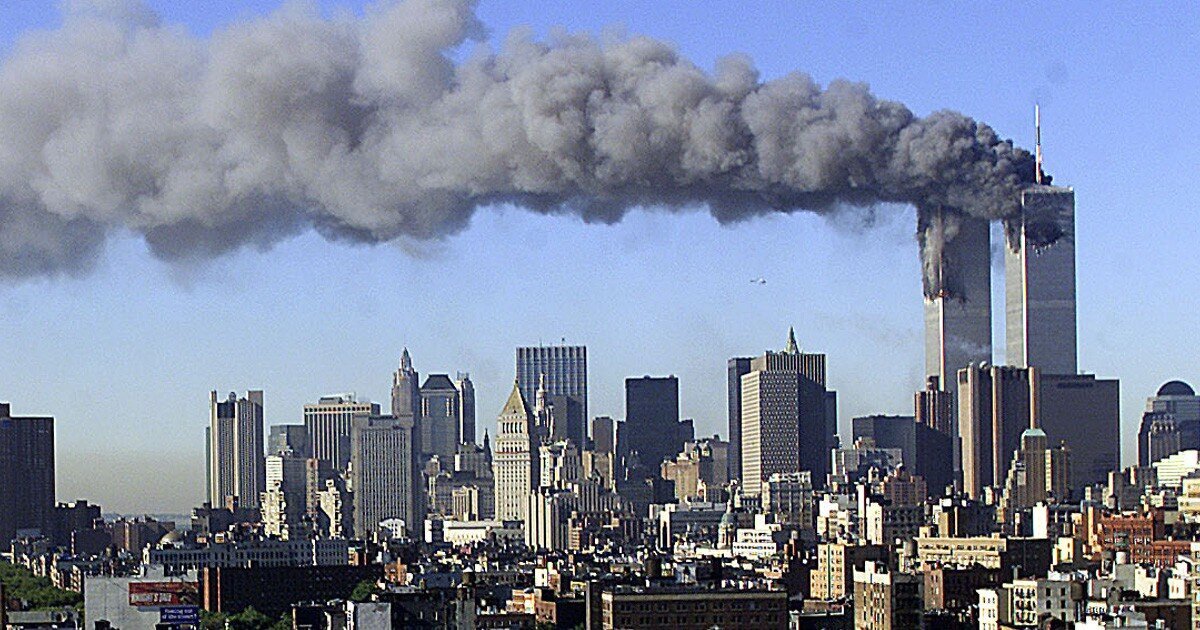

On September 11, 2001 I was visiting church partners in Germany in my role as General Minister and President of the United Church of Christ. As we approach the twentieth anniversary of the terrorist attacks, and following the dramatic collapse of the US backed government in Afghanistan and the return of the Taliban to leadership of the country, I offer the following remembrances of my days in Düsseldorf and Berlin, along with theological reflections on the response of the church over the ensuing two decades.

In the entrance lobby of the Evangelical Church of the Rhineland in Düsseldorf, Germany, a striking piece of sculpture commemorates the Theological Declaration of Barmen affirmed a few miles away at Barmen-Wuppertal in 1934. Emerging from a solid bronze base is a collection of human figures. The majority, standing erect and facing one direction, have their arms raised in the Nazi salute. Behind them, facing away, a smaller group of men, women, and children gather around an oversized open book recalling the words of the first article of the Declaration:

Jesus Christ, as he is attested for us in Holy Scripture, is the one Word of God which we have to hear and which we have to obey in life and in death. We reject the false doctrine that the Church could and should recognize as a source of its proclamation, beyond and besides this one Word of God, yet other events, powers, historic figures and truths as God’s revelation.

The sculpture graphically portrays the Church Struggle of the 1930s in which some Christians in Germany sought to resist the corruption of the German Church by the Nazi party. To those working or visiting in the church headquarters today, the sculpture serves as a potent reminder of the seductions always facing the church as it seeks to remain faithful amid the allure of cultural, economic, and political idolatries and ideologies.

It was this arresting piece of art that greeted me as I arrived for a visit with the leaders of the Church of the Rhineland on September 10, 2001. I was accompanied by our host, the ecumenical officer of the Rhineland Church, the Rev. Christine Busch, as well as Dr. Peter Makari, Area Executive for the Middle East and Europe of the Common Global Ministries of both the United Church of Christ and the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Our visit to Düsseldorf was the beginning of a three country visit to introduce me to United Church of Christ partners in Europe.

This regional church in Germany is part of the Union of Evangelical Churches tracing its heritage to the unionist (Lutheran and Reformed) Church of the Prussian Union in the early 19th century. In 1980 and 1981 the national Synods of the United Church of Christ and the Evangelical Church of the Union (the name of the UEK at that time) entered into a formal church partnership called Kirchengemeinschaft or “church fellowship/communion.” Over the twenty years since the Synodical declarations this relationship had blossomed into numerous Conference-Regional Church relationships, congregational exchanges, youth visits, theological colloquies, and joint mission efforts. As our meetings began, we couldn’t have imagined that within a day the visit would become a profound experience of global ecumenical solidarity and that the indelible image of the Barmen sculpture and its timeless message of resistance to evil and idolatry would accompany me through my years as General Minister and President as the United Church of Christ.

Following our visit with the church president, Manfred Koch, and his colleagues in Düsseldorf, Peter and I traveled to Berlin where we spent the night at a church hotel in central Berlin, the Dietrich Bonhoeffer Haus, named for the famed Lutheran theologian and Confessing Church leader martyred by the Nazis in 1945. Our hotel’s name was another prompt to the memory of the Confessing Church members’ courage and resistance in the face of tyranny. An evening stroll revealed little remaining evidence of the wall and security zone that once divided the city near our hotel. But the glass-domed Reichstag building glowing in the evening darkness and the Brandenburg Gate reminded us of the violent history that consumed Germany and the world during the Nazi and Cold War periods.

The next day, September 11, took us to Frankfurt (Oder), a small city on the Polish border where we began our day with a visit to Global Ministries personnel, Stephen and Lisa Smith. The Smiths were serving in local congregations and, in addition, Stephen helped support the Ecumenical Europe Center, a ministry focused on relationships between German and Polish churches. The presence of their young son David added a delightful element to the morning visit in their home. The day would end on a profoundly different emotional plane.

Our primary purpose for visiting Frankfurt (Oder) was to present an award to the Superintendent of the Cottbus District of the Evangelical Church of Berlin Brandenburg. Superintendent Rolf Wischnath was to have received the Global Ministries Award of Affirmation at the joint General Synod/Assembly of the United Church of Christ and the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), to which he had been invited as our international partner from the Europe region, earlier that year in Kansas City, but was unable to attend. He was being honored in recognition of his ecumenical work for peace, justice and non-violence and in particular for confronting a resurgent right-wing movement in Germany. The award ceremony was marked by a classic experience of gemültlichkeit – a delicious luncheon, wine, toasts, music provided by the award recipient playing his baritone horn, and a convivial gathering of guests. Because of his very public ministry in his church district and its political significance, the local news media was present. It was a lovely and relaxing time after two long days of travel and meetings.

Toward the end of the event, we noticed the reporters on their phones. From their expressions it was clear that something of newsworthy significance was happening. We assumed, of course, that it had little if anything to do with us. But then Superintendent Wischnath was called over to speak with the reporters and the celebration was suspended as he came to us and informed us that they were receiving reports of terrorist attacks in New York. We were quickly taken to a car and driven to the news station where we were offered phones to call colleagues and family in the United States and settled into a studio where we could watch the video feed of emerging events in the United States. It was there that we saw in real time the impact of the second plane on one of the Towers. A young reporter sat watching with me, tears running down her face.

As the only Americans readily at hand we were asked for on-air interviews. I recall very little of what the interviewer asked or what I said, except this: “The violence so many in the world experience on a daily basis has now come to the United States. I hope that our response is to be drawn into a deeper sympathy and solidarity with the vulnerable ones around the world, that we will not retaliate by simply inflicting our own violence on others.” Perhaps it was not so clearly stated as my memory is now seeks to reconstruct. Yet however it was articulated at the time, it expressed a sincere hope. No doubt it also reflected a fear of how American political leaders and an aggrieved and enraged public were likely to react. Sadly, in the coming months and years those fears were tragically realized. Sitting in that studio, aware at that point only of the lives likely lost in the World Trade Center, we could not foresee the twenty years of violence in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere this day would provoke. But I’m sure that even then I sensed the moral danger we were facing amid the powerful allure of vengeful and self-righteous retaliation. How would the American church respond?

After a day that had begun so joyfully, Superintendent Wischnath bade us a sad farewell and we began the ninety minute journey back to Berlin. Along the way we learned that an ecumenical memorial service was being planned for that evening and that I would be invited to be present and offer a prayer. The hastily organized event was hosted by the Cardinal Archbishop of Berlin, George Sterzinsky, and our UEK colleague, Bishop Wolfgang Huber of the Evangelical Church of Berlin-Brandenburg, and later Chairperson of the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD) Council. We gathered at the historic Berliner Dom, the so-called Protestant Cathedral in central Berlin. Built at the turn of the 20th century, the Berliner Dom had been almost completely destroyed by Allied bombing in May, 1944 and only fully restored by the early 1990s. The massive sanctuary was full, with government ministers and officials occupying the front pews. My role was largely symbolic, Cardinal Sterzinsky and Bishop Huber being the principal officiants. But the invitation, gracious and heartfelt, expressed the importance of the United Church of Christ partnership to the German Evangelical churches. And it offered these church leaders an opportunity to stand alongside a representative, however unofficial, of a bereaved nation.

The service, of course, was conducted in German with the exception of my brief prayer, which rendered me primarily a spectator. For me, the most moving part of the evening took place outside as we emerged from the cathedral where I stood with a government minister to greet members of the congregation as they filed out. A German military officer spoke of his friendship with Colin Powell as if he expected me to greet Secretary Powell on his behalf when I returned home. It was a somber, almost surreal experience. But beyond us in the large square in front of the cathedral were hundreds, perhaps thousands, of young people who had gathered, holding candles and singing. I tried to sense the mood of those young people. Sorrow? Hope? Fear? Determination to resist evil? Perhaps all of these. Thinking of them today, now in their middle age, I wonder what that night meant to them, how it shaped the years ahead as it has shaped the ensuing two decades for me.

Peter and I made our way back to the Dietrich Bonhoeffer Haus, its name again reminding us of other historical events that took place nearby and how one theologian offered guidance to the church in the choice between the Gospel and “blood and soil.” As we passed the United States embassy, we noted mounds of flowers piled up by the entrance. Not since before the Vietnam War had the United States engendered such sympathy and international support. Would we be able to avoid squandering it?

Our original itinerary included a morning meeting on the 12th with Bishop Huber and other church leaders including some who had played influential roles in the establishment of Kirchengemeinschaft years earlier. Our route to the meeting took us past the famous Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church. Next to the modern church, built after World War II, stands what remains of the original church building destroyed by Allied bombing. The jagged teeth of the decapitated bell tower reminded me that September 11, 2001 was not the first time terror from the skies had rained down death and destruction on a city. Again, the question posed itself: Would we in the United States be able to see ourselves as more than victims, but as part of a global community of vulnerability and suffering that calls for healing and understanding rather than further violence?

Embracing me at the door to our meeting room, tears on his face, was an old friend, Rev. Reinhard Groscurth, the retired ecumenical officer of the Evangelical Church of the Union in the western part of Germany who, with his colleague, Rev. Christa Grengel in the east, had played such a critical role in the establishment of our church-to-church relationship during the 1970s. I had met Reinhard on several of his many visits to the United Church of Christ. An exceedingly kind and gracious man, his presence was a profound pastoral gift after an emotionally draining twenty-four hours. I remember little else of that meeting. Certainly, we must have shared the many reports we had already been receiving from our Conference Minister colleagues in the UCC about the amazing outreach and support they were receiving from their partners in the various regional churches across the UEK.

Also, in addition to the obvious reflection on the role of the church beyond 9/11 which must have taken place, several people present described the 90th birthday party they had attended the day before for retired Bishop Albrecht Schönherr. Schönherr had been a member of the Confessing Church, studied under Bonhoeffer at the famous underground seminary in Finkenwalde, and ended the war in a prisoner of war camp. He later became the bishop of the Evangelical Church of Berlin-Brandenburg, its territory mostly within the German Democratic Republic. Schönherr led the church in its delicate relationship to the socialist state under Soviet political and military control. In Cold War East Germany, largely secular, Schönherr guided a church shorn of its pre-war state-church status in learning how to become, in Bonhoeffer’s words, “a church for others.” Many credit Schönherr with forging a church community that was able to provide the safe space for Germans, particularly young people, to gather as they sought an end to Soviet domination and national division. These reminders of the Confessing Church and of the theology of Dietrich Bonhoeffer over those two days were no doubt the prompt for me to make Bonhoeffer my principal theological reading partner through the ensuing years of my term as General Minister and President.

That afternoon we were taken to Potsdam, at one time the home of Prussian royalty and, in 1945, host to General Secretary Joseph Stalin, President Harry Truman, and Prime Ministers Winston Churchill and Clement Atlee for the conference that determined the administration of Germany following its surrender. Today it is famous for its palaces so popular with tourists. But our visit was to a more modest church where we were to attend another special memorial service for the victims of the previous day. By this time, we had become more aware of the magnitude of loss in New York, Washington, and western Pennsylvania. The powerful memory from this event was the presence of the members of the Potsdam fire brigade in their firefighting outfits ringing the square around the church in silent vigil to their fallen comrades in New York. Whether it was simply the fatigue from two exhausting days, or the recognition of the enormous sacrifice by first responders in New York, this was, for me, the most emotional moment of the time in Berlin.

As was the case the night before, many of the people who crowded the church that day were young. The great care of the presiding clergy to explain each portion of the liturgy as well as the context for each reading made it clear that most in the congregation were infrequent worshippers at best. Yet on this day they were drawn to the church, searching. Searching for what, it was not clear. At the close of the service we were invited to come forward to take a candle, light it, and then place it somewhere in the church. I watched as these young people moved with their candles through the sanctuary. Some took a long time to decide where to leave them. These young people had come of age during the heady optimism of the end of the Cold War, the demolishing of the wall, the reunification of Germany, and the rise in opportunity, especially for youth in the former east. They had also watched other significant world events, including legal apartheid crumbling after the release of Nelson Mandela from prison and his election as President of South Africa. For many I suspected, the attacks of 9/11 were their first encounter with the reality of evil that had not been fully vanquished. Could it be, I wondered, that they are seeking some secure place to plant their hope on a day when their youthful optimism had been profoundly shaken?

Our time in Germany was drawing to a close. Commitments with the World Council of Churches and the World Alliance of Reformed Churches in Geneva, and with the Reformed Church in Hungary in Debrecen and Budapest beckoned. We departed for Geneva from the famous Tempelhof Airport in the center of the city with its iconic 1930s architecture familiar to many who watched old World War II movies. On the way to the airport we passed one more memorial, this one to the Berlin Airlift of 1948/49 when British and American planes sustained West Berlin’s population after Soviet authorities cut off all access to the western half of the city. Tempelhof was the eastern hub for the airlift. The memorial is in the shape of an incomplete arch, its three arms reaching toward the west pointing to the air corridors used by the planes where, symbolically, they are met by identical monuments reaching toward the east on the sites of airfields where the flights to Berlin took off. To be sure, the Berlin Airlift was more than just a humanitarian effort. The intense geopolitical competition of the Cold War from both east and west was the primary motivation for the Airlift. Nevertheless, nations learned that raining down clothing and food on a starving city still reeling from the devastation of war could preserve freedom more effectively than bombs.

The two pieces of sculpture that framed these three remarkable days have helped me reflect on some of the lessons from a horrific act of terror and the two decades that followed. The Barmen sculpture at the offices of the Church of the Rhineland sets the choices starkly before us. To whom is the church ultimately obedient? The Theological Declaration of Barmen puts it this way:

The Christian Church is the congregation of the brethren in which Jesus Christ acts presently as the Lord in Word and Sacrament through the Holy Spirit. As the Church of pardoned sinners, it has to testify in the midst of a sinful world, with its faith as with its obedience, with its message as with its order, that it is solely his property, and that it lives and wants to live solely from his comfort and from his direction in the expectation of his appearance. (Emphasis added)

We reject the false doctrine, as though the church were permitted to abandon the form of its message and order to its own pleasure or to changes in prevailing ideological and political convictions.

Upon my return to the United States, I found a country awash in an aggressive, jingoistic, and unreflective patriotism. I was astonished to see churches festooned with American flags. A drive through my own home town in Connecticut revealed home after home, business after business, decorated with American flags far beyond any display I’d ever seen on the Fourth of July. Most American churches of all denominations accepted an Evangelical President’s rhetorical framing: “A war on terror,” “An axis of evil,” “You are either with us or against us.” Within one short week of the terrorist attacks the United States Congress authorized the use of military force in Afghanistan with little debate and only one member voting against. A crusade was underway laden with religious symbolism. Reminiscent of the Vietnam era of my formative years, the patriotism expected of the country allowed for no critique, no nuance, and certainly no reflection on how the exercise of American power in the previous years had contributed to this moment. The flag itself took on idolatrous religious significance.

Ironically for those of us who have seen an independent press excoriated by many, including President Trump over the past four years, the mainstream media following 9/11 seemed to lose its journalistic nerve. Editorial cheerleading for a violent response not only on the terrorist groups themselves, but on an amorphous group of global enemies prevailed. Throughout the roll-out of the duplicitous administration rationale for the invasion on Iraq, and what I called then “Words of Mass Deception” about the illusionary weapons of mass destruction, the media seemed to abandon its sharp, investigative role. And in both Afghanistan and Iraq the media allowed itself to be “embedded” with the military, almost guaranteeing there would be profound limitations on journalistic independence.

In my experience, few pastors of any denomination took to their pulpits in 2001 or even in the ensuring years to directly challenge the “prevailing ideological and political convictions.” Even in churches like the United Church of Christ, with its longstanding commitments to justice and peacemaking, theologically driven misgivings about how America was responding to the terrorist attacks often were allowed to be silenced by the perceived need to attend to “pastoral concerns.” Where prophetic courage prevailed in pulpits, the majority in the pews responded in stony silence if not angry dissent. In 2007 at the United Church of Christ General Synod I along with the other officers of the church read a pastoral letter reflecting on the church’s failure. It included these words of lament:

We confess that too often the church has been little more than a silent witness to evil deeds. We have prayed without protest. We have recoiled from the horror this war has unleashed without resisting the arrogance and folly at its heart. We have been more afraid of conflict in our churches than outraged over the deceptions that have killed thousands. We have confused patriotism with self-interest. As citizens of this land we have been made complicit in the bloodshed and the cries. Lord, have mercy upon us.

And what of my hope that the experience of violence on our shores would deepen our sympathy and sense of solidarity with the millions around the world who suffer violence every day? Twenty years on from the terrorist attacks Americans still persist in seeing their September 11 violation as exceptional. Even the use of torture at Abu Ghraib and elsewhere, or the endless imprisonments of Guantanamo, or the indifferent incompetence of our post-war administration of Iraq, or the war crimes of some of our own soldiers and contractors, have not shaken our confidence in the exceptional nature of American virtue.

Here theologian Reinhold Niebuhr offers instruction and warning, albeit from a book written fifty years earlier about the contest between western democracy and communism:

It is very dangerous to define the struggle as one between a God-fearing and a godless civilization. The communists are dangerous not because they are godless but because they have a god (the historical dialectic) who, or which, sanctifies their aspiration and their power as identical with the ultimate purposes of life. We, on the other, as all “God-fearing” men of all ages, are never safe against the temptation of claiming God too simply as the sanctifier of whatever we most fervently desire. Even the most “Christian” civilization and even the post pious church must be reminded that the true God can be known only where there is some awareness of a contradiction between divine and human purposes, even on the highest level of human aspirations. . . . If we should perish, the ruthlessness of the foe would be only the secondary cause of the disaster. The primary cause would be that the strength of a giant nation was directed by eyes too blind to see all the hazards of the struggle; and the blindness would be induced not by some accident of nature or history but by hatred and vainglory” (The Irony of American History, 1952).

The death and disruption we have spread across the Middle East over these past twenty years teaches us nothing if not the dangers of a trumped-up national vanity unchecked by a faith that reminds us that God’s purposes always elude our full understanding and that certainties about divine justification may only veil national arrogance or political expediency.

Among the writings of Dietrich Bonhoeffer that I read over the ensuing decade is a haunting little piece written at the end of 1942 to his fellow conspirators in the effort to assassinate Hitler. Titled “After Ten Years,” Bonhoeffer concludes with a penitential paragraph that could very well speak for much of the American church at this moment in history:

We have been silent witnesses of evil deeds. We have become cunning and learned in the arts of obfuscation and equivocal speech. Experience has rendered us suspicious of human beings, and often we have failed to speak to them a true and open word. Unbearable conflicts have worn us down or even made us cynical. Are we still of any use? (Letters and Papers form Prison, Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works, Volume 8, p. 52).

Are we still of any use?

The question should haunt us. Twenty years after this so-called war on terror began in response to the 9/11 attacks it has cost tens of thousands of American lives lost or permanently diminished. Hundreds of thousands of Afghans and Iraqis, both soldiers and civilians, have been killed or wounded, and trillions of dollars have been diverted from domestic purposes such as schools, housing, health care or the building of a robust public health service that could have saved so many lives during the pandemic. It has distracted us from rapidly accelerating income inequality, the growing catastrophic threats of global warming, the resurgence of white supremacy, and the rise of an anti-democratic kleptocracy enabled by the political influence of the obscenely wealthy. Much of the population of the Middle East is more insecure than ever. Now as the last United States troops leave Afghanistan to its seemingly inevitable fate, all of this hardly seems a price worth paying for the grisly trophy of Osama bin Laden’s corpse.

Bonhoeffer is famously remembered for saying, “We are not to simply bandage the wounds of victims beneath the wheels of injustice, we are to drive a spoke into the wheel itself.” There were, of course, those in the church who offered up resistance, who spoke out, who dared to challenge the vanity and lies underlying America’s ill-considered crusade. There were those who did experience America’s suffering as a call to more fully embrace suffering and violated people elsewhere. But far too many in America’s churches played cheerleader to America’s folly. Far too many became silent witnesses. Far too many have grown cynical rather than courageous and hopeful. Far too many forgot that the pastor is always to be the prophet, that to sever the prophetic vocation from the pastoral calling is to abandon the latter altogether.

Sixty years ago, long before 9/11 and even before the church and the synagogue struggled with the moral dimensions of the war in Vietnam, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel wrestled with the nature of patriotism and the prophetic vocation: “What motivates the prophet is God’s attachment to Israel, and Israel’s failure to reciprocate. To save the country was the aim of their mission, but the mission itself was to re-establish the relationship between Israel and God.” Heschel went on to speak of the false prophets, so evidently legion now in our own time:

These reassuring seers of good things were minions of monarchs and favorites of the people. The confidence with which they predicted peace, if it cannot be traced to their flattery of princes or to their corruptibility, must have had its roots deep in the instincts and affections, in a certainty of divine protection for what normal man cares most about: life, country, security. Samuel, Nathan, and Elijah had already declared that God was no patron of kings, and the great prophets uttered threats not only against kings, but against country and nation, thus challenging the conception of God as the unconditional protector and patron. (The Prophets, 1962, pp. 423-424).

Heschel might have been speaking as well of German Christians who surrendered their faith in the Biblical God to the Führer. Or he might have been speaking of even the Confessing Church which recognized too late the peril facing their Jewish neighbors. And he may have also anticipated the American Church of the Twenty-first century that either advanced or allowed the messianic vision of George Bush and his neo-con court prophets. In 2005 on a trip to India, when so much more was known of the moral bankruptcy underlying the response to 9/11 and the unfolding disasters that were to come, I was asked by a bishop of the Church of South India, “How is it that you re-elected George Bush?” How indeed.

Are we still of any use? The Barmen sculpture places the question of allegiance at the center of any response. On the twentieth anniversary of the terrorist attacks the church will of course want to remember the victims, those who died and those left behind. But if the church truly wants to answer Bonhoeffer’s question and face its own actions in the years since, it must pose to itself this question: “Is Jesus Christ, as attested to in Scripture, the one Word of God we are to hear, trust and obey in life and in death?” Or do we persist in allowing “other events, powers, historic figures and truths” to stand for God’s revelation?

As we face this question, the second memorial seen on my visit offers its own witness. The Berlin Airlift memorial at Templehof was, perhaps, a fitting final image from three remarkable days. At a personal level, it spoke to the amazing embrace we experienced, this time as it were from “east to west” rather than the original “west to east.” Church leaders, young people, reporters all touched us with their compassion and concern. Far from home in the midst of crisis, we were not alone. How can global, ecumenical solidarity embrace the lonely and vulnerable of our world with a similar embrace?

Second, the memorial in Berlin reaches toward two identical memorials across what was once a divided country. Could the anniversary remembrance of 9/11 prompt us to consider how we reach across other walls, finding common cause with those who, in the language of the New Testament, seek to “break down dividing walls of hostility?” Third, the planes that delivered food, clothing, coal, medicine and other supplies to Berlin in 1948 and 1949 were in many cases the same sort of planes that just a few years before had delivered death and destruction to Berlin’s citizens. Could we not exploit a similar imagination to discover ways to respond to the world’s continued violence with reconciling and life sustaining payloads rather than retaliatory violence often unleased these days from unmanned drones? Finally, the Airlift memorials bear the names of seventy-seven British, Americans, and Germans who died in crashes during the flights. Peacemaking always involves some cost. Will we be willing to bear it?

Others had far more remarkable and often devastating experiences in the days around 9/11, many in New York or at the Pentagon or in thousands of homes where an emptiness and grief still remain these many years later. My own experience was remarkable for the confluence of people, encounters, physical monuments bearing deep historical resonance, and whatever meaning I have been able to take from them. It was a deeply privileged experience for which I remain very grateful. But above all, it has left me with images that hopefully have sharpened my own sense of moral clarity along with a deepened awareness of the moral dangers and seductions that always lurk close at hand.